In the golden age of newspapers, the high priests of publishing built cathedrals of power across America. They commissioned the celebrated architects of the day to build iconic buildings symbolizing authority over the press, the people, their communities and history itself.

It’s over. Today, newspaper buildings designed by some of world’s greatest architects are being abandoned or sold. Surviving properties are valued more for their real estate than their public purpose. Economics favor tearing them down for parking lots or converting them into condos.

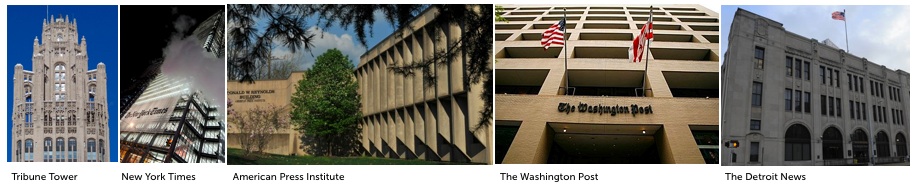

The dismantling of the news industry’s landmark architecture occurs throughout the U.S. claiming even the contemporary architecture of the modern news business. The New York Times Co. moved into a new 52-story headquarters designed by Italian architect Renzo Piano but sold the building and leased back a few floors to pay down debt. Gannett and USA Today have leased parts of their stark, twin towers in Washington’s suburbs to at least five other companies. Last week, The Washington Post announced it will try to sell its iconic, 63-year -old building in downtown Washington. That would complete a Capital District three-fall where Marcel Breuer’s Bauhaus masterpiece, the American Press Institute in Reston, Va. was vacated in January.

But to see ambition reach for the sky only to fall to the ground, you must go to Chicago. Here is where the once proud and powerful Tribune Co. is emerging from bankruptcy with a coming asset sale that will likely include the landmark Tribune Tower. A sad fate awaits the “Cathedral of Commerce.” Built by an authoritarian publisher as a symbol of his empire, Tribune Tower has passed from an owner who flips real estate to new owners — creditors, two investment firms and bankers — who aim to sell parts to pay off debt.

Tribune Tower was built in 1922 by Col. Robert R. McCormick, the publisher of the The Tribune and a grandson of its founder. Like Pope Julius II, who in 1505 commissioned Michelangelo to create a tomb for him of unparalleled power and grandeur, McCormick sought to stir a 20th Century renaissance in a city where the architecture of the Industrial Age flourished. He created a turning point in American architecture with an international competition to design the most beautiful office building in the world.

The winning architects, John Mead Howells and Raymond Hood, combined the traditional elements of the engineering marvel of the day, the skyscraper, with the imposing architectural influences of Europe’s cathedrals: soaring spires, flying buttresses and grotesques. Tribune Tower was built as a tower of religious power. Newspaper publishers everywhere wanted one. And so they built them.

There is more to this than nostalgia for grand buildings and the indignity of decline. It’s personal, not just for me but for the thousands of newspaper journalists who once filled the empty desks of our newsrooms. I was reminded about the connection between architecture and common purpose when the Detroit’s two newspapers announced last week that they were abandoning the historic The Detroit News Building built in 1917 by Albert Kahn, “the architect of Detroit.”

I worked at The News in the ‘90s and redesigned Kahn’s elegant assembly-line into a newsroom modeled on a vision of a wired village. Change overtook history. I left The News for an Internet job before the new newsroom was completed. My payment: Kahn’s original blueprints.

After reading the obituary on The News Building, I emailed the link to my friend Mark Silverman. “No mention of Peskin’s newsroom design, just that Kahn guy” I wrote. Mark, who lived in the newsroom as editor for eight years, emailed back: “Kahn created arches. You created community.”

That’s a legacy I value more than seeing a new idea become old. I’ve become comfortable with the incomplete, just as I have come to terms with moving toward the new before the old becomes obsolete. So must those who still live the mythology of newspapers.

The cathedrals that came to embody the progressive values and moral authority of industrial America are slipping away. Their forms, either the classicism of the past or the streamlined modernism of the present, proclaimed a faith in controlled efficiency and the power of authority.

We now proclaim a faith in the power of us all. We hold the new cathedrals in our hands. How we use them completes the unfinished architecture of our future.