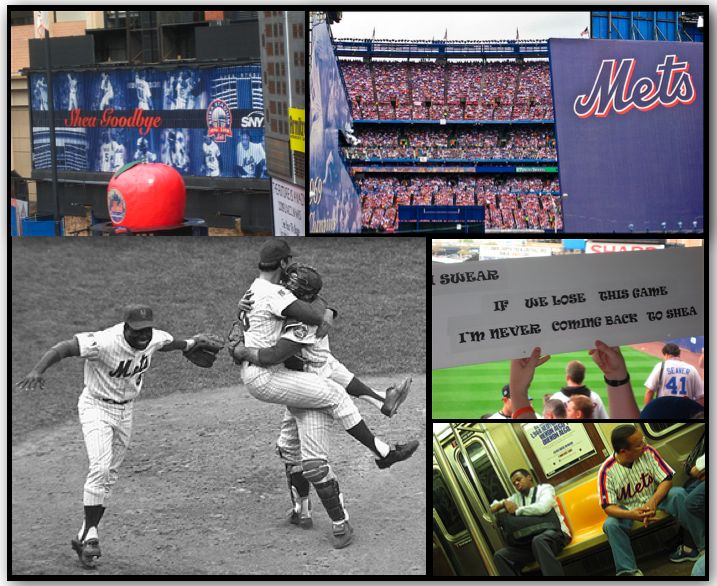

Photos: Creative Commons via Flickr from Bobster1985, lisatozzi, jeffpearce and Annie Mole.

The practice of professional journalism is like the practice of professional sports. It’s physically demanding, dirty, and success requires a combination of skills, talent, experience and luck.

But it’s different in one glaring respect. Sports fans love their teams, the players and the sport itself, whatever it may be. They may jeer and boo when they are disappointed, but eventually they forgive. Love brings them back. News fans – well, there are none. News is a necessity, but it’s hard to find anyone who loves, truly loves, a news brand.

U.S. newspaper companies have struggled for a decade or longer to fight the social forces and technologies that have crushed their business models. The Internet has shattered old monopolies on news, information, advertising and trust. The answer from the newspaper industry has been an endless game of catch up and defense while losing revenue, marketshare and cultural relevance. But the real failing of U.S. newspapers has been the disintegration of their brands. As brands – as institutions that reflect and inspire passion, commitment, loyalty and investment from customers – U.S. newspapers can hardly sink any lower.

But they can rise again to play another day, another season. They can learn from baseball.

The lesson from baseball for the news industry struck me like a foul ball to the forehead when I attended the final weekend of play for The New York Mets at Shea Stadium last weekend. Let me stipulate apologies to readers around the world who couldn’t care less about baseball. I’m writing about my team, the only one that’s really mattered to me over the years. I’m not a rabid fan. I’m not all that into sports at all. So if you can’t relate to American baseball, or the Mets, I hope you can think of something else that resonates in your life. Imagine a product, experience or place that you love. It’s something that defines you not simply as a user or consumer – but as a fan.

In defense of nobodies from nowhere

It’s easy to mock journalists and the institutions that employ them. While many aspire to ideals of fairness, accuracy and completeness, failure on all fronts is inevitable. Some of the failure is avoidable, but some is simply the nature of the beast. Humans are imperfect. Their stories are imperfect. Their story-telling is imperfect. The first rough draft of history will be corrected, cleaned up, revised and reinterpreted later. Daily journalism is messy.

And messier: the daily has given way to the perpetual. The deadline is now. The once-a-day broadcast or newspaper has transformed, in theory, into a slower-paced, higher-value, artistically inclined craft experience packed with the cultural relevance and production values of weeklies, monthlies, books or feature films.

But of course they haven’t. Theory gives way to reality. Because daily journalism remains so messy, so imperfect, it remains easy to mock the process and product itself. Shallowness, simplification and irrelevance become painfully obvious around election time, when political campaigns and debates inevitably get boiled down to a race to the finish. The story of the race is the story of who’s in the lead at the moment. He said, she said, polls show. Winners, losers. You’ve heard it all before and you’ll hear it again.

But what’s worse than the failures of the process are the pious denials and defenses from its producers. A charade of righteousness permeates American journalism. I have heard multimillionaire U.S. newspaper CEOs boast of the social and political importance of their companies, and suggest that if they fail as businesses then society and democracy fails with them. I have heard newspaper editors talk, seriously, with straight faces, about the printed newspaper as a place for deeper analysis. They imply that text and images published on their web sites are somehow less deeply analytic than when published a day later on paper. It’s an incomprehensible claim, a bald-faced lie from people who are supposed to be defenders of truth and guardians of trust.

A legion of academics and lesser-paid worker bees – professional journalists and opinion makers – have guzzled this elixir and are rolling drunk on it. They continue to stress the distinction between their work, swaddled in professional values, credentials, integrity, virtue and mystique, and that of the anonymous, brain-dead horde – everyone else. Us. Them. “They” are nothing more than amateur sycophants, pundits and opinion mongers lacking the experience, expertise, influence and clout of real journalists. That’s my summation, my words, echoing the disbelief I heard five years ago at our first We Media conference, which angered some professional journalists and brought others to tears. The arrogance lingers on. Gene Weingarten, a columnist for The Washington Post Magazine, wrote a month ago: “The Web, after all, is already filled with self-celebratory maunderings of nobodies from nowhere with nothing to say; Facebook and MySpace are dedicated to exactly that.”

The baseball way: With Love

Ordinary people see the difference between professional reporting and analysis and amateur hour – and they also see and reject the relentless arrogance of professionals who think so highly of themselves and so little of everyone else. Our research at iFOCOS has found two-thirds of Americans are unsatisfied with the quality of the journalism in their communities, but they haven’t yet turned to blogs as their first source for news. Traditional institutions remain the primary source for news and information, ordinary people recognize this and they hunger for better products from those institutions.

But what’s a better product? Given the inherent challenges and shortcomings of daily and perpetual journalism under the best of circumstances, what could possibly reverse the disdain most Americans express about the media? Or, for that matter, the disdain that professional journalists express about nobodies from nowhere? What kind of news people and news products would we nobodies not merely tolerate and consume against our better judgment, but truly love and cherish?

This brings me back to baseball. Some say baseball answers all of life’s riddles. I don’t know about that. But it offers an answer for newspapers.

Last weekend I drove with my two sons from Virginia to New York to attend the final weekend of New York Mets baseball at Shea Stadium. The team is moving to a new stadium next year.

I grew up in New York City loving the Mets, not the Yankees, in the ’70s and ’80s, and Shea was the physical home of those memories. I loved Tom Seaver, Nolan Ryan, Dave Kingman, Dwight Gooden and Darryl Strawberry. I also loved taking the No. 7 subway to Shea Stadium in Flushing, and I loved the grungy feel of Shea and the sense of closure when I walked down the ramps from the upper deck cheap seats to head back home after the game. I brought my sons to New York to share something of that with them.

We lucked out – we attended Saturday’s game, when ace pitcher Johan Santana delivered a superstar performance – a three-hit shutout against the Florida Marlins. This kept the Mets’ playoff hopes alive. Throughout the game we watched videos presenting memories of the stadium from former players and from fans. Jerry Koosman, the pitcher who won the final, winning game of the 1969 World Series for the Mets, threw the honorary opening pitch. The fans in the stadium loved every minute of it.

Here’s the astonishing part about all that emotion sparked by a game, a place, a team and a sport: the Mets lost nearly as often as they won. Since Shea opened in 1960 the team’s record there was 1,859 wins, 1,713 losses. The team’s champion seasons of 1969 and 1986 were anomalies and stood out because most other seasons were either dismal or frustrating. Time and again the team failed, but fans stuck with them and new fans emerged.

The day after my sons and I watched them win, the Mets lost and failed to get into the playoffs. The season and team history at Shea ended with a fitting close: disappointment.

But it also ended with something that newspapers seem incapable of inspiring or exhibiting: love. That’s a useful benchmark for any business, but it’s particularly apt for newspapers. Mistakes, errors, omissions and disappointments are assured. Love can heal.

The enduring news businesses of the future, like those of old, will exhibit and inspire love from real fans. I have no doubt it’s possible – just like I have no doubt that the Mets will try hard again next year. They may screw up, but the fans will be there to cheer them on.