Clemens, Kindle and Congress: History rhymes

History may not repeat itself, but it sure does rhyme, observed Samuel Clemens. I was reminded of Clemens’ vision and failures amid this week’s hoopla over the new Kindle as well a Congressional hearing held today on the crisis in newspapers.

Clemens was a visionary who foresaw the age of invention. He wrote a glorious fable about a time traveler from contemporary America who used his knowledge of science to introduce modern technology to Arthurian England. As a book publisher, Clemens also set out to solve a long-standing problem with technology. Anticipating the advent of mass production and mass media, he invested in a mass-media production machine, the linotype, the most significant machine for printing since the invention of moveable type.

Like a jumping frog from Calavaras County, the linotype leapfrogged the hand-powered technologies of the day. But getting the frog to jump far, and often, on demand was a problem the technology couldn’t solve. Society changed faster than the machine. The linotype, expensive to build and buy, required continual investment to spread publishing to the masses. And while the linotype would become the essential machine for book and newspaper publishing for nearly 100 years, Clemens’ investment depleted the fortune made from his writings.

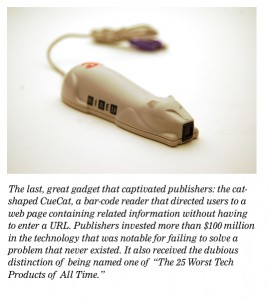

History rhymes. The new Kindle is a latter-day linotype machine. Amazon’s latest e-ink reader delivers a thin, mobile screen optimized for the size of a standard sheet of paper, large enough for newspaper and magazine publishers to maintain traditional format for articles and advertising. Cool, but will the gadget save newspapers? No way.

The Kindle represents the latest incarnation of a dreamy, aspirational future for newspapers: no physical distribution costs, little competition, and a steady revenue stream that comes from consumers.

As a cost-buster, publishers love the potential. Theoretically, they could eliminate costs associated with materials and manufacturing systems for news production: typesetting, composition, plate-making, newsprint, ink, presses, sorting belts, and delivery trucks. While those costs vary from one publisher to another, internal sources and past experience put them at between $300 and $600 per subscriber, per year. Say you’re a mid-sized publisher with low-production costs and 50,000 subscribers, that’s a savings of about $15 million a year. If you’re The New York Times, with high production costs and 1 million subscribers, that amounts to about $600 million a year.

At $489 per Kindle you could give one to every subscriber and save money by getting out of the printing business. The problem is that most subscribers won’t buy and don’t want a Kindle. Nor are enough readers apt to buy a subscription to a newspaper on the Kindle.

At the high-end, Amazon currently sells a subscription to The Times for $14 a month. That version delivers a black-and-white facsimile of the printed Times with fewer features than the paper’s free Web site, no interactivity, no video, no sharing, and just one update a day. Not much of an experience. Amazon gets a 70 percent cut of subscription revenue and rights to republish to other devices. It would also get a cut from the deals publishers like The Times make with advertisers for the device. Some deal.

The Times doesn’t even make what editor Bill Keller calls “real money” from the Kindle: something substantially less than TimesSelect, the premium content service the Times killed after its revenues of about $10 million cost them more than that in lost advertising.

Now companies such as Hearst are planning to charge for premium content on the Kindle that consumers won’t read for free on Hearst websites. So, too, is Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp., which has assembled a team to create a device like the Kindle to deliver content from The Wall Street Journal, The Times of London and The New York Post. For News Corp. and other newspaper companies, the move is a clear break from a decade-long strategy to offer news content online for free and monetize it through advertising.

The economics aren’t good; the business strategy baffling. Moving content to a closed, proprietary device like a Kindle could quickly kill whatever is left of the newspaper business. Without a better alternative, no publisher in his right mind would abandon printed newspapers and give up the revenue from print advertising, no matter how bad the print business looks.

We’re now designing an environment where every surface is becoming a screen – monitors, walls, windows, counters, tables, art, desks, computers, phones, even entire buildings. Why settle for gadget too long in development (the promise of e-ink is about ten years old) that delivers an inferior experience for a product that may be obsolete? Better to adapt an important mission to ways that inform society today.

More significantly, there’s a platform that reaches almost everyone. No investment in the costly, old infrastructures of printing is required. It’s called the Internet.

It’s painful to watch publishers come to terms with the shift the Internet has brought. It can’t be downloaded on a Kindle, or even on their Web sites. While the Internet changed the world, it didn’t change the way newspaper publishers think. They still tend to think of it in terms of devices like the Kindle: computers, cell phones, gadgets and networks — the extensions of industrialization and automation of the workplace and market. They see the Kindle and want to Amazon the news. They  see an iPod and want to iTunes the news. They see an iPhone and wonder if an app can spread their stories. They look at Google and think someone is stealing their content and their money.

see an iPod and want to iTunes the news. They see an iPhone and wonder if an app can spread their stories. They look at Google and think someone is stealing their content and their money.

The sad fact is the current condition of newspapers is the result of something much bigger that’s going on as well as the inabiity of newspaper publishers to understand it

The Internet is neither technological nor media phenomenon: it is a social phenomenon. We live in a time when technology enables society to organize, as well as to be informed, in wondrous ways as individuals. The emergence of personal, digital technocracies replaces the long-powerful idea of the Industrial Age, which organized the masses around the efficiencies of mechanical systems. “Mass production, mass media and mass marketing are all based on the premise that human beings can fall into place as cogs in highly mechanized systems and then behave with great predictability,” writes media, tech and culture expert Douglas Rushkoff in his book, Get Back in the Box. “Efficiencies in production and distribution are the priorities. Over the past 150 years, this strategy has succeeded in growing some of the largest and most profitable businesses the world has ever seen. At the end of the Industrial Age, they are collapsing around us.”

No matter what set of metrics you apply to measure them, mass production, mass media and mass marketing are all in decline. That is because the basic organizing principle of the Industrial Age — that technology should be used to manage the masses — is just over. If newspapers go down, they ought to produce a legacy for something’s that better. Clay Shirky did a good job of laying out the problem earlier this year, saying: “Society doesn’t need newspapers, it needs journalism.”

As business leaders who are failing, publishers now turn to friends in government for help – just the way they did when they had to compete with other newspapers in the same city. In 1970, they convinced Congress to pass the Newspaper Preservation Act, which authorized the formation of joint operating agreements among separate competing newspaper operations within the same market area. The act was designed to exempt newspapers from antitrust laws to allow the survival of multiple daily newspapers in a given urban market in the face of declining circulation. This exemption stemmed from the fact that the alternative for at least one of the newspapers, generally the one published in the evening, was to cease operations altogether.

Boy, didn’t the Newspaper Preservation Act work out well?

Today, at a hearing on the future of journalism hosted by the Senate subcommittee on Commerce,  Science and Transportation, Dallas Morning News Publisher James Moroney asked Congress for a limited antitrust exemption to allow the newspaper industry to work together to find a way of making money online. Which is another way of admitting, again, that publishers can’t figure it out on their own.

Science and Transportation, Dallas Morning News Publisher James Moroney asked Congress for a limited antitrust exemption to allow the newspaper industry to work together to find a way of making money online. Which is another way of admitting, again, that publishers can’t figure it out on their own.

Moroney said newspapers could do something they’ve never been able to do before: work together to persuade Google and other online titans to pay them more for links to newspaper stories. “If we do that as an industry we’ll have clout,” Moroney said.

Three words: New Century Network.

Once again it’s about clout. The question is: whose got it now? History rhymes.