The story of what happened somewhere, told by someone who was there, is as old as cave painting and as ordinary as a cute cat video. Yet it’s still provocative, potent and revolutionary. It’s the foundation of what we call news, and also of freedom, justice, politics, knowledge, communities and culture. It’s what we talk about around the campfire and on Twitter. It’s what dictators fear most. It’s how the bible got started. Bearing witness is an act of defiance against anyone who claims authority over the truth.

But truth is a tricky thing, and so are photos and videos that purport to capture it. They are puzzles, raw material for fiction and nonfiction. A picture is worth a thousand words because it takes that many to explain it. What happened before and after the shot? What was unspoken, unheard or off-screen? Who is in it? What’s their story? Who made it? Why? Is it real or fake?

These are the ordinary uncertainties of digital life. The questions themselves reveal a kind of digital literacy, a baseline of doubt and skepticism about what we know and how we know it. Photos and videos aren’t stories in their own right. For that you need a story-teller.

Last summer on Staten Island, where I grew up, a bystander captured video that showed a New York City police officer lock his arms around a man’s neck. “I can’t breathe,” the man, Eric Garner, said before he died. This spring, videos of a catastrophic earthquake in Nepal competed in social feeds with images of protests in Baltimore, where another video, shot a couple of weeks earlier, showed the arrest of Freddie Gray, a young man who had fled from the police, was subdued, thrown into a police van and later died from a severe injury to his spine. Last week, a video showed a white police officer draw his gun and tackle a black teenager outside a pool party in McKinney, Texas.

All of those scenes were the consequence of circumstance, shot on phone cams by witnesses who happened to be there. It’s still a stretch to say cameras are everywhere, but not a big one. It’s now normal to see the world through unfamiliar eyes and from strange angles.

Police – at least those that do bad or stupid things in public – are apparently still figuring out what others take for granted: we are watching them. Surveillance, a tool of the state, is also a tool of the people.

But surveillance alone is never enough.

Like a photojournalist, but adamantly not one, Devin Allen showed the intentional eye of a story-teller in the images he shot during the Freddie Gray protests in Baltimore, his hometown. The 26-year-old posted a series of black and white photos to his Instagram account, which flooded with tens of thousands of followers and viewers, among them music superstars Beyoncé, Erykah Badu and Rhianna, who shared one of his photos with her 17 million Instagram followers (she’s now up to 20 million).

One of the photos landed on the cover of Time magazine, then in a stream of quickie posts about the amateur who shot the shot on sites such as Business Insider, BBC, Fusion, the Washington Post and Petapixel, the photography blog where I first learned about Allen’s cover shot.

The fascination with the shot, which someone at Time thought was such a big deal that they issued a press release about it, was reminiscent of the momentary fascination with The New York Times in January when it featured Instagram photos of a snowstorm on the newspaper’s front page.

Does any cover on any newspaper or magazine matter? More importantly, what does it mean to matter? To whom? To a publisher or editor who sees it as a visual device to attract web and mobile audiences, social shares, adjacent advertising and even single copy sales of the printed thing itself? To media owners and investors who seek to minimize expense? To a young photographer whose work “blows up,” goes viral and is seen by millions of people? To a reader who sees it, shares it, discusses it and learns something because of it? To a designer who conceives and toils over it? To a society that seeks meaning, action and catharsis from the stories we tell about ourselves?

In Baltimore, as his city convulsed between rage and grief, Allen was no mere observer. He was there for his city.

“At first, I was getting a lot of heat from photojournalists,” he told Time. “But no more. Some photographers even apologized because they didn’t understand what I was trying to do. They didn’t understand that I wasn’t a photojournalist; I wasn’t trying to be one. I was just documenting and showing things from my point of view.”

I was just documenting and showing things from my point of view.

That’s one way a photo or video matters, isn’t it? On a magazine cover, in Youtube or a social stream, it offers a singular, personal view of what happened.

In the age of mobile social digital everything, with cameras everywhere and photos of everything shared by everyone, the news remains personal. It’s our story no matter how we come across it, no matter who sells it. Who cares where a photo was “published” first; or second or third when it was curated and redistributed by a friend of a friend, or by media brands and pop stars with huge audiences; or even how it reaches us? It matters when when we see and feel what happened through someone else’s eyes. Professional or not, and no matter where you encounter it, the stories that matter most are inherently personal.

The first-person story is only recently the raw material – the “source” – for a business, called journalism, and for professionals who collect, verify, organize, interpret, package, pretty-up and promote it. There’s still a robust market and cultural hunger for news, now primarily on screens and even if the economics that support it aren’t what they used to be. But the authors of the first rough draft of history are now the people who saw it, spoke it and uploaded it, not the reporters, editors, aggregators and curators who arrived later and sold it. Within days of the Freddie Gray riots the Maryland Historical Society announced it would collect photos and oral histories from people who were there.

We’re confronted with a curious juxtaposition: a photo on a famous magazine’s cover, shot by a talented and previously unknown photographer who doesn’t want to be called a journalist, is more symbolic of how news “happens” in 2015 than the once iconic magazine itself. The cover travels on its own, detached from the pages beneath. But the photo and its story travels further, shared in an app, detached from any publisher’s business model or brand. It wasn’t a Time magazine cover. It was a Devin Allen story. The messenger is the message.

#Welovebaltimore is the movement we snatched all the kids off the streets for a big cookout and fun ::: No help from the city ::: But we are pulling out all stop ::: #ripfreddiegray #DVNLLN A photo posted by KnownNobody ?????? (@bydvnlln) on

Photos:

-

The May 11, 2015, issue of Time magazine with Devin Allen’s cover shot from Baltimore, photographed in a Harris Teater supermarket news rack wth other magazines in Reston, Virginia. Photo by Andrew Nachison

-

A sampling of photos uploaded to Flickr and tagged “Baltimore” and “#blacklivesmatter”

-

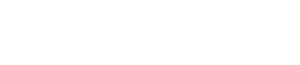

“The Kiss” by Alfred Eisenstaedt, Life magazine, August 27, 1945, via Pinterest Aka V-J Day in Times Square

-

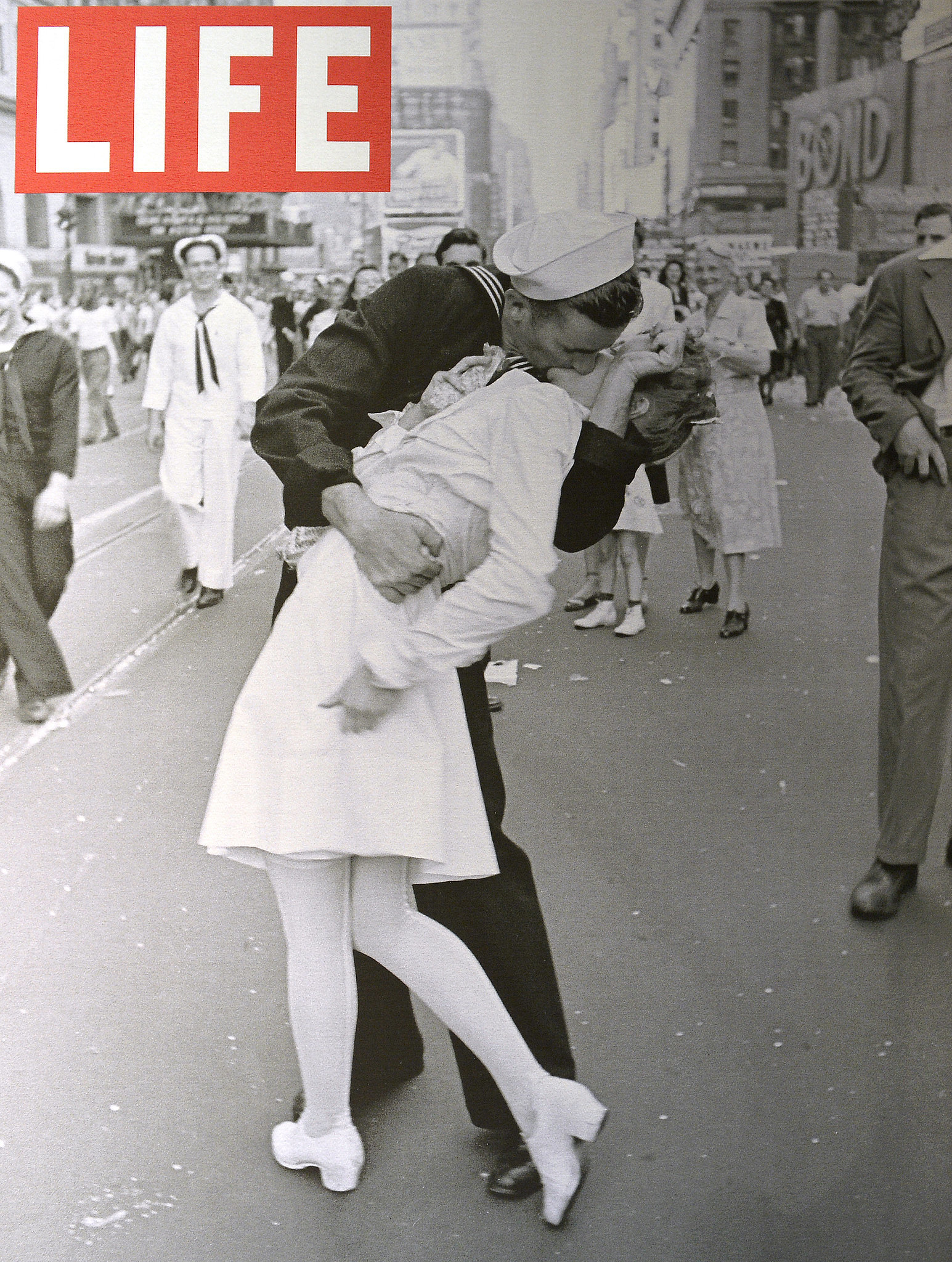

Caitlyn Jenner photographed by Annie Leibovitz, June 2015, Vanity Fair

-

Photos of Baltimore by Devin Allen via Instagram