The revolution within the revolution: How mobile devices and social media changed Tunisia

Before we get all Twittered about the events in Tunisia, let’s put the Jasmine Revolution in perspective. After decades of repression and economic turmoil, a citizen’s act of defiance sparked a people’s uprising that ousted an oppressive regime. Citizens demonstrated. Citizens were killed. Citizens changed their government. Let’s not trivialize them as gadgets or hashtags.

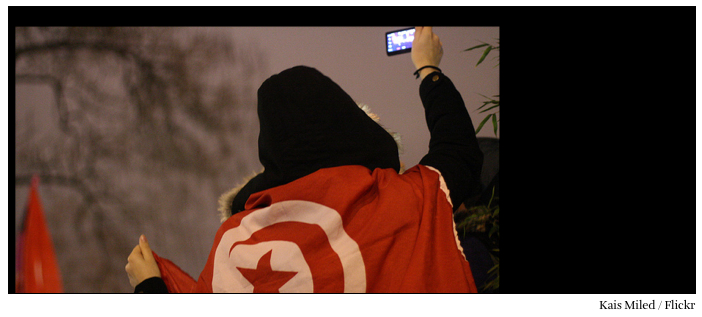

What is revealing about this revolution is the way in which citizens discovered it, how they informed one another, and how they mobilized around it. They used their mobile phones, now ubiquitous in North Africa, to communicate via text messaging and Twitter.

For many Tunisians, their phones are their Internet. Theirs is a story about the democratization of media, a social revolution that wields the power to change lives as well as governments. It has authoritative regimes throughout the world very worried. Some are using the very technologies available to the masses — friends lists, phone logs, geo-location apps, facial recognition — to locate and identify dissidents, spy on them, punish them. Repression 2.0. Technology is making democracy more dangerous, not less.

We are just beginning to understand the implications of the social revolution that is redistributing power throughout society. Spread person-to-person by mobile devices, unrest mounted amid Tunisia’s newly connected generation outside the glare of network TV cameras.

The revolution was not televised but tweeted. It occurred with a suddenness that exposed the shortcomings of traditional media throughout the world. What simmered in Tunisia for a month went largely unreported by a diminished and increasing parochial mainstream media. Only Al Jazeera, the Arab-language news network based in Qatar, seemed to recognize the growing tempest in Tunisia and the implications for the rest of the Arab world. By reading the blogs, following the tweets and using its mobile phones, Al Jazeera found signs of political ferment both in Africa and in the Islamic world fed by economic distress, political repression, and young people with the tools — including mobile phones and Internet — to make changes.

“I am certain its (the revolution’s) success is entirely correlated to the ubiquity of the mobile phone and the Internet,” blogged Aly-Khan Saatchu, an investments banker based in Nairobi. “I recall a friend and an ambassador telling me, “Aly-Khan, the revolution is coming.”

Tunisian dissident Bechir Blagui, who runs the website Free Tunisia, told a Huffington Post blogger that cellphones and social media were crucial to information flow that helped protestors gather and plan their demonstrations.

“They called it the jasmine revolt, Sidi Bouzid (the site of the first clashes) revolt, Tunisia revolt .. but there is only one name that does justice to what is happening in the homeland: Social media revolution.”

In the U.S, blogs and Twitter provided the best way to watch events unfold. On the ground in Tunisia, bloggers from Global Voices Online began posting daily developments in December after an unemployed Tunisian set himself on fire to protest joblessness, sparking the populist uprising against the government. On NPR’s news blog, social media master Andy Carvin curated posts, tweets, video and other media. The Twitter hashtag #sidibouzid served as a universal link to the latest information from social media correspondents around the world.

As a realtime source of news and information, the significance of Twitter in Tunisia’s citizens’ revolt is itself an issue of confusion and debate, the fodder for blogs and Tweets among media theorists and foreign policy wonks.

With each leap in communications technology the medium plays a more significant role as an instrument of the people, whether for a personal connection or a political action. More than just a means for knowing and reporting, our media connect behavior with action. And that is a revolution within a revolution.