Why the mega-stories matter

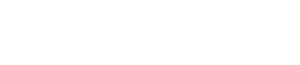

Last month, The Guardian published a digital showpiece, an elaborate, painstakingly crafted microsite focused on a single story and presented to show off the British publisher’s design, technical and story-telling mastery as well as its “ownership” of a complex work of journalism that, by virtue of its special treatment, the Guardian’s editors signaled was more important than others.

NSA Files: Decoded advanced the state of the art of rich, narrative, multi-perspective web journalism.

Like a number of similar story-telling blowouts from other publishers, NSA Files was striking both for the care of its production and for how far it departed from the norm in online news.

It wove text, graphics and videos about the U.S. government documents leaked by Edward Snowden into a simple, mobile-friendly scroll – with no advertising or any of the usual distractions encountered on “ordinary” online news pages. The story, unlike most, was designed to be read and viewed with concentration, to woo, inform and delight an audience through a “lean back” and time-demanding experience. It was like a well-designed print magazine. But unlike a series of ambitious failures from magazine publishers who had pinned high hopes on the design-friendly reading experience of iPad apps, NSA Files was easily viewed and shared in a web browser on a computer, tablet or smartphone. It was native to the web.

Stories like NSA Files are exceptional, and this is why they matter. They are stretches. They are creative bursts in a sea of sameness. They are a proof of life. They offer hope for the future – and also a hint at what the next generation of digital news products could look like, and how they might demonstrate distinctive value, rather than simply claim it.

Senior content and strategy executives I’ve spoken with at a variety of news operations in recent weeks tell me they are expanding their use of photos, videos, maps and interactive data tools in routine stories. But singular, special blow-outs like NSA Files are too expensive and too difficult for everyday stories. That’s also why they are important. The mega-stories show us not only what everyday stories could look like, but what using them could feel like.

The return of design

Although still uncommon, well-designed online story pages started appearing a few years ago, first in mobile apps and then in web sites inspired by them. Spacious, easy, distraction-free reading is the defining characteristic of a variety of mobile apps that aggregate and re-format stories from publishers, such as Flipboard and Zite, or “save for later” reading apps such as Instapaper and Pocket. It’s also the most obvious feature of Twitter founder Evan Williams’ new web publishing platform, Medium.

The “reader” toggle in Apple’s mobile Safari browser attempts to provide a pleasing reading experience when publishers don’t, and a number of publishers have re-imagined their web designs to improve the experience not only on mobile browsers but on any browser. Quartz, Slate, National Journal, The New Republic and USAToday have all re-designed their web sites in the past year with mobile-inspired story pages that are easier to read, easier to navigate and just easier and more pleasant to use than more cluttered designs they now clearly outclass.

They share a few common traits: Larger and more spacious text, fewer distractions and less “noise” surrounding articles, slender navigation bars at the top and icons that contain and hide drop-down navigation and site tools.

But virtuoso web productions of individual stories are still rare, even from the biggest news publishers whose web sites are often limited, and sometimes crippled, by chaotic and unforgiving templates, awkward publishing tools, conflicting business goals and the relentless crush of continuous production.

A micro-burst of experiments in story-telling and design is a sign of curiosity from companies that have spent the past decade looking inward, managing down expenses, setting up paywalls, chasing after audiences on social networks and figuring out the finer points of photo slide shows and other forms of link bait.

The business of news, dwindling except for those who seek to overtake it, has overshadowed the practice, craft and creative fringes of online journalism.

So experiments in new story-telling styles and better ways to present distinctive, differentiated, long-form reporting are daring, icy shocks to the system. Their mere existence, even from an elite publisher like The Guardian, signifies success for their creators and overshadows annoying quirks like auto-play videos and slow-loading pages – and complaints that they are over-blown vanity projects, full of “superfluous bells and whistles” so ego-driven journalists can strut their stuff. Yes, they are. It’s also what distinguishes them from those who have no stuff to strut.

Something neat

Last year, an even more ambitious story production from The New York Times, Snowfall, was viewed more than 3.5 million times in its first week online, suggesting rich, non-fiction digital story-telling had finally “arrived.” The Times enhanced its reputation, earned bragging rights – and won a Pulitzer Prize.

“People heard that The Times was doing something neat; they came in droves; and they stuck around for a while,” the newspaper’s executive editor, Jill Abramson, gushed in a memo to her staff.

A number of technical advances, such as open-source code to simplify production of interesting image-and-text scrolling effects, made it likely that more Snowfalls would follow. And they did. The Times published The Jockey earlier this year. Rolling Stone, Grantland, Pitchfork, USAToday and The Wall Street Journal have all produced similarly showy stories with screen-spanning images and a mix of text, video and funky scrolls.

Polygon, a gaming blog from Vox Media, took the concept even further just this month: Its exhaustive reviews of the Sony Playstation 4 and Xbox One gaming consoles featured not only beautiful type, illustrations and scrolls but screen-filling advertising that elegantly appeared and disappeared during the scroll. Polygon also applied the same visual language found on the web page to the animated video review embedded within it.

For now, these projects matter because they are outliers – visually distinctive rarities, painstakingly compiled over a period of months by teams of reporters, photographers, designers and developers. Like The Serengeti Lion, an extraordinary production from National Geographic, they stand out in an ever-expanding web universe of chaotic, jumbled news pages we endure but rarely enjoy. Those “regular” pages are engineered to meet the needs of publishers, not readers, to earn money with a jillion links scattered everywhere.

Some think the mega-projects are a waste of time for everyone – including the audience.

“I suspect that years from now, we’ll look back at “Snow Fall,” “The Jockey,” and their copycats in the same way we now regard 1990s-era dancing hamster animations—as an example of excess, a moment when designers indulged their creativity because they now have the technical means to do so, and not because it improved the story or readers’ understanding of it,” Wall Street Journal tech columnist Farhad Manjoo wrote in Slate.

I see the opposite, or at least its possibility: A turning point for online news, a moment when editors, writers, photographers, videographers, developers and designers converged to express creative instincts that had been suppressed for so long their mere appearance was a sensation. These stories, imperfections and all, herald a potentially game-changing new direction for online news: thoughtful reading and viewing experiences baked into higher-value journalism, higher-value stories and higher-value productions in every encounter with every story and every page.

Multimedia isn’t the future, it’s the past

Collectively, the recent story-telling mega-projects have breathed life into a dream as old as the web: that complex, immersive multimedia stories will become routine for professional newsrooms that produce them and for audiences who love and value a thrilling mix of story-telling and technical wizardry.

But it’s an old and mostly unfulfilled dream, at best naive and, at worst, completely misguided for a world of commoditized, social, mobile mass media on ever smaller screens.

I say this not as an indictment but a lament. It was my dream. In 2005 I published a collection of essays and illustrations from a group of designers and visionaries about the emerging art of digital story-telling. (The Flash version of the book is no longer online, but a copy of the print book is available from Google Books).

“We are a decade into the visual Web,” I wrote in the introduction. “Digital story-telling is NOT new, is NOT unexplored terrain in the new communications frontier.”

I’m still hungry for new designs, formats, story forms and reading experiences that feel inherently “webby.” But in a world drowning in stories from professionals, eye-witnesses, social networks and marketers, I’m less sure of what news should look like, let alone what it inevitably must look like, where it belongs or if anybody other than dreamers really cares.

I saw my first Mosaic browser window in 1995. Ever since then I’ve expected that the unlimited potential of the World Wide Web would inevitably lead to “better” forms for journalism – and that they would be complex, non-linear, multi-media extravaganzas. I don’t know what I meant by this, only that the old, discrete forms of story-telling – text, images, sound and moving pictures – could be combined in new ways on screens. I imagined something like Snowfall, not an article with two tweets and a video embedded in the middle.

Stories could have many different entry points and pathways – and this “non-linear” approach had to lead to some new, deeper and more intrinsically digital, “webby” and better form for news. I reasoned, or departed from reason and fantasized, that some new odyssey of the imagination would provide not simply “different” forms of stories, but better ones. I thought the early web’s linear approach – its realism – would give way to cubism, abstract expressionism, something wild and post-modern – or at least The Wizard of Oz.

I don’t know why I expected so much out of my computer screen, or why I thought there would ever be a business model for news-as-art. I imagined the early web of text, sound and photos, and even the “less early” web of blogging, was like the silent film era, or the first days of television – that something colorful, with music, lighting, multiple camera angles, drama and emotion, was bound to emerge as a new and distinct form.

I still hear this dream in people who say we’re “early” in the era of digital media. But we aren’t. In retrospect, my references to Hollywood, entertainment and art were more apt than I realized – just not for news and journalism. Complex, self-directed, non-linear, immersive, emotion-packed full-screen multimedia digital experiences have truly arrived – just not for news, or the web. Anybody who has played Halo or pre-ordered Destiny knows this. Video games, which eclipsed the film industry’s revenue and production budgets five years ago, have in many ways fulfilled the craziest story-telling fantasies I and others used to attach to online news. Just not for news. To put Snowfall’s traffic triumph in perspective: In September 2013, the game Grand Theft Auto V earned more than $1 billion in its first three days of retail sales.

Online news, and the needs and expectations of its mobile, social, info-saturated devotees, is no more like video gaming than it is like Hollywood entertainment. The crumbling business model of news has pushed production budgets lower, not higher; and users have shown a preference for speed and brevity over depth and detail. So instead of becoming more complex, news businesses have maintained relatively simple production processes built around the work of individual writers, photographers and videographers. News products have fragmented into simpler, sharable components: headlines, links, lists, summaries, shortcodes, likes, tweets, photos, videos, infographics, animated GIFs, maps, memes and comments.

Like a multi-directional video game, this makes the social news experience deeply personal. Individuals, rather than editors, directors or executive producers, choose their own paths, compose their own narratives from the assortment of texts, images and social cues encountered in browsers and apps. Narratives are only barely and briefly contained by publishing brands and their money-making pages. They are also deconstructed and shared out, liked, pinned, tweeted, discussed and excerpted elsewhere. The web itself, rather than mega-projects like the Guardian’s NSA Files, has become the non-linear “roll your own” story canvas.

Although there was once an expectation that news publishers would need or at least want to flex their creative and journalistic muscles to establish a distinctive experience and value for their digital audiences, they have for the most part focused on a simpler and easier course: extract revenue by any means possible through familiar story forms and clever headlines to drive audiences to them. Dreams of multimedia moonshots gave way to the industrial realities of routine production.

On a practical level, it’s obvious why “big” stories are so rare. They are big. For sheer scale alone, they are more expensive to produce than routine reports, even investigations and features that take months of reporting.

The story environment itself – everything from the typography to the layout of the page – breaks the mold of standard templates. When I say “template” I don’t mean it as a metaphor for a pattern or model or workflow. I mean, literally, the forms and code that content management systems use to display content on web sites. Most advertising-supported web sites dictate pages flooded with links and ads. They depend on templates engineered to drive revenue, not to tell a story or please a reader.

My old multimedia mega-project fantasy for online news ignored a deeper truth about people: the story forms I expected to improve upon were never lacking or outdated. Writing, photography and film making (now video making) have flourished on the web. They are webby.

Multimedia story-telling has undoubtedly arrived, only in a much simpler form: the web is filled, every day, every second, with text, photos, videos, maps, infographics and social media articfacts. Nearly two decades into web culture, online publishing remains dominated by old forms that have proven resilient and powerful. These are the elements of everyday stories, all easily produced and combined by anyone with a smartphone.

The only thing that hasn’t flourished, yet, is putting them all together. That’s why the mega-stories matter.

With 41 percent of US newspapers charging a subscription fee for access to their web sites, and other publishers around the world doing the same, the mega-stories offer a glimmer of hope that news businesses can figure out higher-value products and user experiences. Story-telling, still the core of media and publishing, is a good starting point for the next round of product innovations. The mega-stories matter because they suggest a possible future for the businesses that make them possible in the first place.