Actor Tom Hardy (The Dark Knight Rises, 2012, The Revenant, 2015) stars in Taboo, a gripping, dark, fictional, literally gut-wrenching period drama on BBC1 television in the UK and the FX Network in the U.S.

Its underexposed grimy cyan hues, story and set location has many viewers, including me, hooked. But there’s something else, a backstory sub-plot portraying a people with mystic rituals. I know them well and they’re a treasure trove of stories.

Taboo’s plot sees Hardy’s character, James Keziah Delaney, back from the dead in Africa to reclaim his late father’s wealth and property. But his father’s nemesis — and there appear to be many in cholera-infested London, including the powerful East India (Tea) Company — want rid of him. They’re also after the deeds he owns to a strategic piece of land, Nookta — a trade route off Canada and America. Delaney is not selling. Conspiracy and gutting murders abound in this 1814 drama.

Presented as a working class flaneur, Delaney incurs frequent flashbacks witnessing and wrestling with a juju witch doctor and rants incantations often in a trance-like state. The show’s thick white fog, blood and savagery scenes conjure up passages from Joseph Conrad’s hellish Heart of Darkness.

From a number of personal observations the show’s creators — Hardy, his father Chips and Steven Knight — found their African source material from a real country, Ghana, or the Gold Coast as it would have been known back then to British merchants. There’s the unfamiliar language, which has fans asking if it‘s real. It is. Twi (pronounced tree) is spoken by the Ashanti people (Asantes), one of Ghana’s dominant cultural groups.

The show’s end credits provide evidence of Hardy’s tutors, The Cultural Group.

Then there’s the appearance of bird markings, carved too, on Delaney’s back. Tribal markings are not uncommon amongst many African tribes, though parts of Delaney’s decorated skin looks more Amazonian Indian, than Ashanti — poetic license, after all it is a fictional drama. The bird, Sankofa, literally translates as ‘go and fetch’. It symbolizes, similar to Chinese culture, the importance of the past’s influence on the present.

As a a twi speaker, I’ve found myself enjoying trying to translate Delaney’s monologues, as well as the film’s symbolisms. I lived in Ghana for eight years and my father, an Ashanti, was steeped in its customs.

As a journalist and filmmaker, there are other reasons I’m drawn to the series. At a time of emerging nationalism and a populist dissociation with multi-culture, Taboo opens a window of sorts for filmmakers, commissioners and audience’s to absorb themselves in the richness of ethnicity; diversity in a period drama.

Remember the sheer excoriating wonder from Mel Gibson’s Apocalypto (2006), Passion of Christ (2004) and presently Scorcese’s Silence (2016). I often wonder why no one has tapped into the Ashanti’s story.

Taboo‘s portrayal of Africa may to some be recidivist, yet there’s an opportunity to clasp here. In an era of 360 narratives and back story fills, I’m curious to see how far it will go into Ashanti lore. Otherwise, and not withstanding the show’s own narrative, here’s a chance to uncover a wealth of anthropological and ethnographic stories of a formidable people who in Taboo‘s fictional years really governed a hierarchical dynasty, with customs that mixed religion and mysticism.

Yaa Asentewaa

If you were in awe of Chief Buthelezi’s fighters in Michael Caine’s Zulu (1964) then a film about the Ashanti’s succession of wars with the British will resonate large, particularly given the role of one fighter — their queen mother, leader and uber feminist of the 1900s, Nana Yaa Asantewaa. Eventually captured in the late 1900s, she was exiled for 21 years by the Brits to the Seychelles where she died.

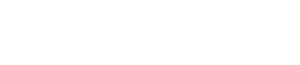

The contemporary images below are from my hard drive but they provide a thread to imagine the world Taboo is acting out.

In the first photo, a King sits, surrounded by his courtiers and royal household. Gold, symbolizing wealth, drapes his arms and neck. Look carefully in the center photo of Blair, then Britain’s PM, shaking the hands of another Ashanti nobility and you’ll notice an aide supporting the chief’s hand. It’s protocol, as well as deference. The chief must not be made to performs tasks by himself.

In historical texts, greetings between Ashanti fighters and others usually occurred using the left hand which was normally reserved for holding a shield. The right hand carried the sword. In the far right picture, a moment of respite; I’m watching on with my brother in customary funereal attire. My father has passed away and his body lay in an open casket at the beginning of an elaborate three-day custom to honor his passing. Christianity and the spirit world, libations n’ all, collide.

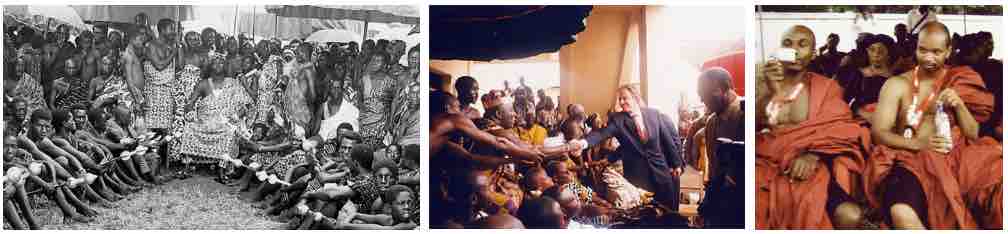

My interests in storytelling took hold when I was ten and sent to Ghana from England to attend boarding school. This sojourn was a trend amongst Ghanaian parents resulting in several students earning the monocle, ‘Been tos’, as in ‘Been to… England, the US or USSR, etc. The school, Prempeh College, was one of the Ashanti region’s jewels. Created in 1949 by Sir Osei Tutu Agyeman Prempeh and a Scottish Eton missionary, Reverend Sydney Pearson, the photo below shows a rare informal friendship between the king and Reverend.

In an interview, Pearson tells us how the two would be wrapped up in thought, sometimes playing with model cars. The middle photo taken in 1977 is Aggrey House — one of eight houses at Prempeh College. I’m in there somewhere.

To the far right, Reverend Pearson in his eighties. We (a school colleague Michael Donkor and I) tracked him down to Carnoustie, in Scotland, where he would recount a set of amazing stories which had us weeping. We cut a short promo, narrated by Jon Snow to tell his story.

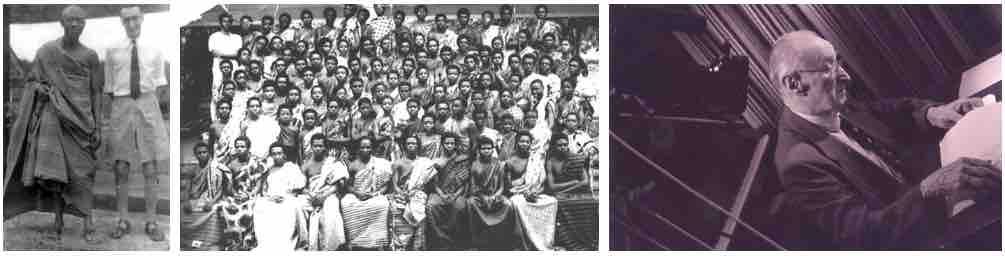

If you look carefully at the far right photo (below), I’m holding a Kodak camera. Aged thirteen at Prempeh College, I became a documentary photographer. The photo on the left is my father and center photo my mother, a National Health Service nurse.

There’s another story here. Ghanaian’s trying to find their feet in London after their country’s independence and the litany of children who would find themselves in the care of foster and adoptive parents.

Taboo and mystic storytelling

Today, I teach cinema journalism, factual filmmaking including news that uses cinema tropes and cues, at the University of Westminster and in rounding off this personal post there’s one last take away from Taboo. Whilst all film, as a theory, can be translated to Freud’s dreamwork (see Unravelling French Cinema by T. Jefferson Kline), Taboo through its spiritism emphatically doffs its top hat to the dynamic conflict theorized in Freud’s ideas of the subconscious (id) and conscious (superego).

Films structured around classic American film narrative rarely possess the courage to become elastic enough to test audiences with their abstraction in the what happens next? — yet at the same time deliver an immersive story. Taboo appears to be doing that, but in a way, whether that’s coincidence or not, mirroring theories behind African storytelling weighted to themes and relational plot devices. Steve Seager’s theory behind innovative models for digital story design gives an idea of this.

Not only does this allow for discursive techniques — e.g. non-linearity — which keeps the audience guessing, but it means the narrative is open enough for others to retell their stories to fill in the gaps.

African storytelling favors mysticism (see Kwah Ansah’s Love Brewed in the African Pot, 1981) and multiple view points. Film forms can be palimpsestic, so can they occupy several filmic structures, hence whilst I’m absolutely not saying Taboo is akin to Ghanian (African) filmmaking, I am alert to its plot line that mirrors Ghanaian folklore story forms. Now that’s something to mine.